Shining Through the Ages: Diamonds in Ancient Civilizations

The geographical origins of unearthed ancient diamonds

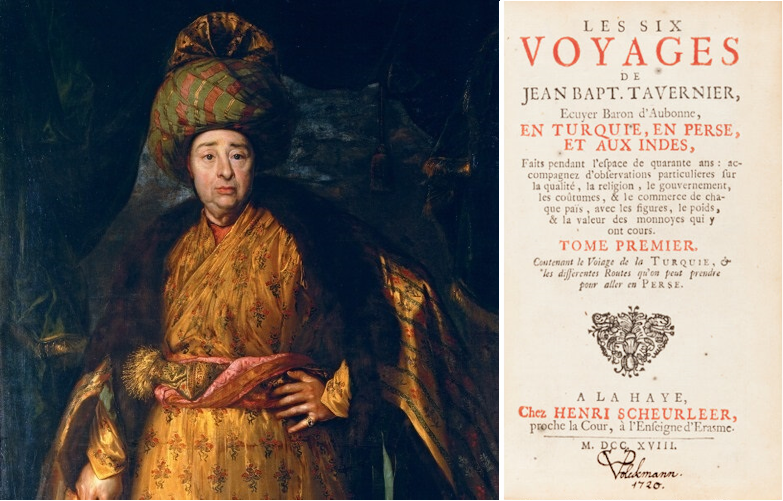

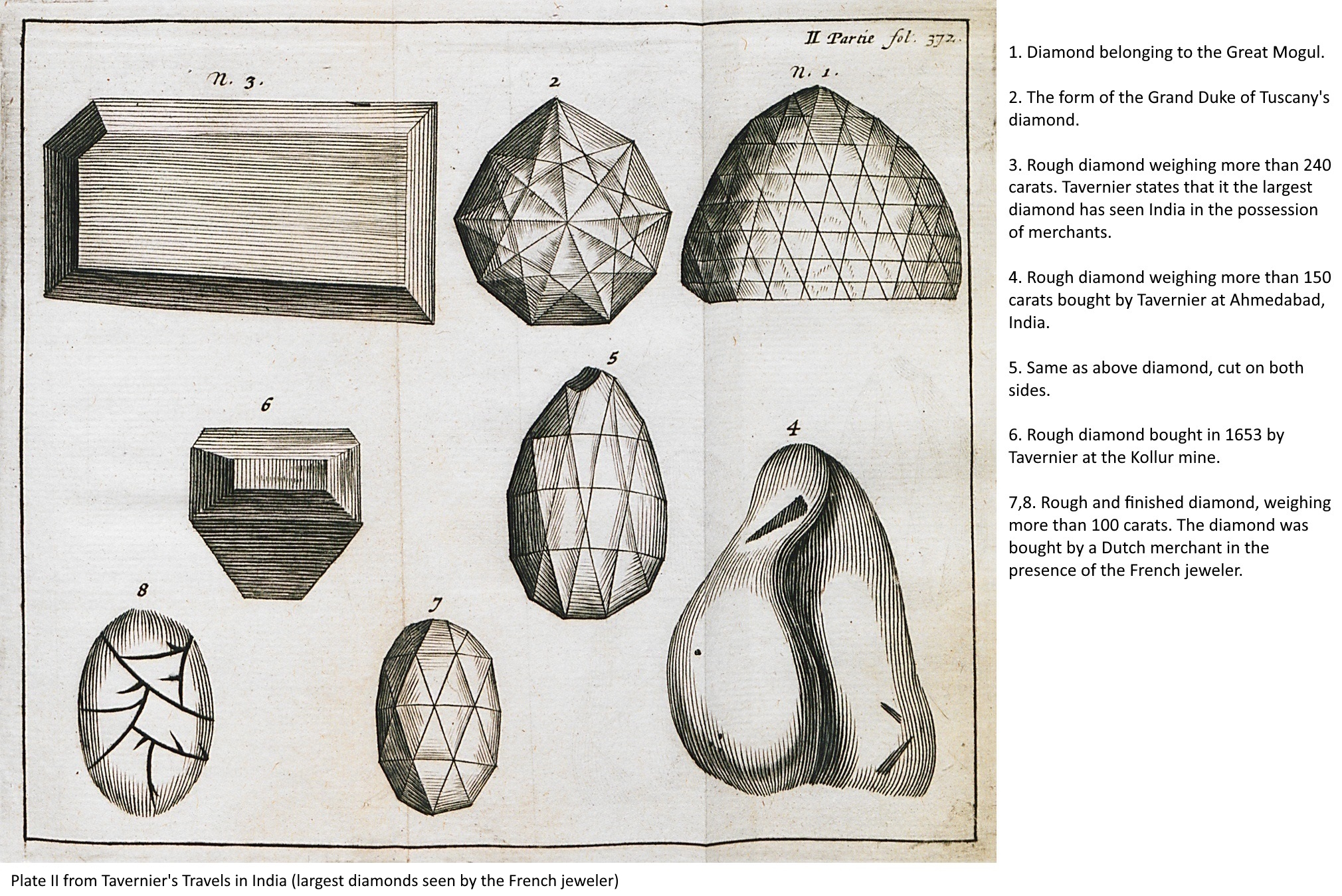

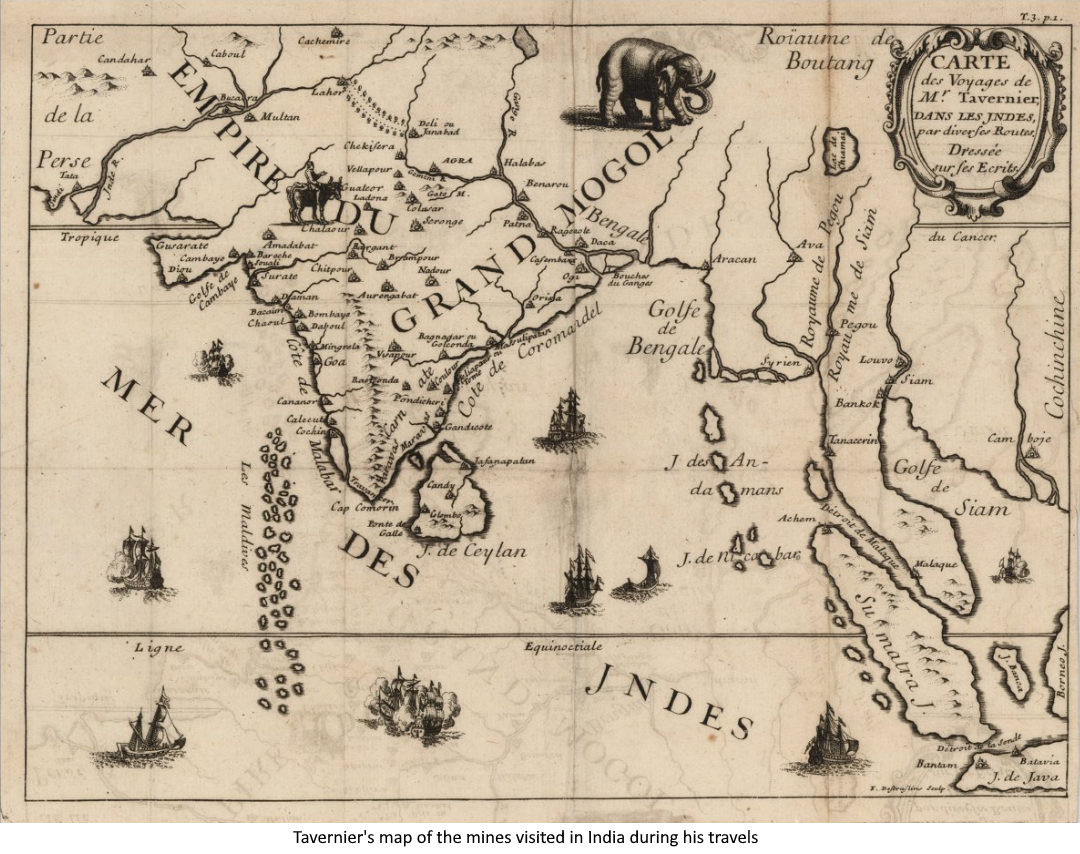

They say it’s about 3000 years ago that man first picked up this unique lustrous stone and realized that it had special qualities: it was so very different from other stones. People began to collect diamonds, worship them, trade them for other goods and eventually wars were fought over them. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, the jeweler and traveler, who traveled to the most distant countries from his native France (Turkey, Persia and India, among others), in his works describes his visits to the mines of India in the 17th century (during his second journey, 1638-43). Tavernier was among the first Europeans to visit the diamond mines, at the time the only ones is existence besides those of Borneo (which he also visited).

Tavernier describes buying huge diamonds from the local miners, the first one weighing close to 50 carats! The miners had to pay a royalty to their king for the permission to mine as well as a percentage of all purchases. Tavernier describes the cutting techniques used in India as inferior to those in Europe, an indication that it was already common to trade raw diamonds from India and then cut them in European cities such as Paris, Amsterdam or Antwerp. Many famous diamonds were brought to Europe by Tavernier, who sold them to Royal families and other wealthy Europeans.

Significance of diamonds in ancient cultures, from India to Rome

Tavernier explains that there was much confusion at the time as to the weight and value of diamonds, as every mine had their own weighing system (mangelins, grains, ratis) which had to be converted into carats, which were also not standardized at the time (there existed Florentine carats, English carats, etc). Also the money used to pay for the diamonds was different in each state, such as rupees in the Empire of the Great Mogul or new pagodas in other states. The French traveler tells us that bartering diamonds for goods such as spices as tobacco was not accepted, only money based on “good gold” was deemed appropriate by the merchants.

The Mahabharata, the Hindu epic poem believed to have be written from about the 4th century BCE, already mentions diamonds. There are two sacred gems mentioned in this work: the Kaustubha (or Kaustubha Mani) and the Syamantaka. The Kaustubha is said to have been worn by the god Krishna ‘the creator and the destroyer of the Universe’ himself (Book 3, Vana Parva: Section CCLXI) and is alternatively believed to have been a ruby. The Syamantaka was also considered to be of celestial origin and is described in more detail in the Harivamsa (chapter XXXVII), considered to be a supplement to the Marabharata. Here legend describes it as being originally obtained from the ocean and passed on between various royal characters as well as being a great source of jealousy and envy.

In Hinduism there are nine gemstones, called Navratna (nava, ‘nine’ and ratna, ‘gems’) representing the nine planets in Hindu astrology, each represented by a God. In ancient India the nobles and rulers believed them to have divine powers and wore them for protection (as we have seen in the Mahabharata). Among these, the ruby represents the Sun, personified by the deity Surya. The pearl represents the Moon (Chandra) and the diamond represents Venus and is personified by the deity Shukra.

Diamonds were also known to the Ancient Romans. In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder mentions diamonds in the book on precious stones (chapter 15 ‘Adamas’, the Latin word for diamond). He says:

The substance that possesses the greatest value, not only among the precious stones, but of all human possessions, is adamas; a mineral which, for a long time, was known to kings only, and to very few of them.

Also underlining its indestructible qualities:

These stones are tested upon the anvil, and will resist the blow to such an extent, as to make the iron rebound and the very anvil split asunder. Indeed its hardness is beyond all expression, while at the same time it quite sets fire at defiance and is incapable of being heated;

Early methods of diamond mining and trade routes

Tavernier describes the earliest methods of mining as he witnessed when he visited the Indian mines (among others the Golconda, Kollur and Soulempour). The diamond veins (ores) which he saw were half to a whole finger wide. The local miners used irons with crooked ends which they thrust into the veins to draw them from the earth. They placed the earth in vessels and later sorted the diamonds from this earth. Sometimes they stroke the rock with such force, in order to extract the earth, that they risked fracturing the diamond which gave rise to flaws. When the miners saw a flaw they immediately cleaved (split) the stone, which meant the weight of the diamonds was lower than it could have been had the miners extracted them in their original size.

The diamond cutters were located at the mines themselves, unlike in modern times, where the raw diamonds travel great distances before being cut. They placed the diamond on a steel wheel and used an incessant flow of water to find the grain of the stone, then used oil and diamond dust to cut the stone, not unlike the techniques that are still used today. Tavernier notes that their cutting techniques were inferior to those used in Europe as their wheel did not turn as fast. Consequently they were not able to give the diamonds the brilliant polish as Europeans were able to do.

Trade routes

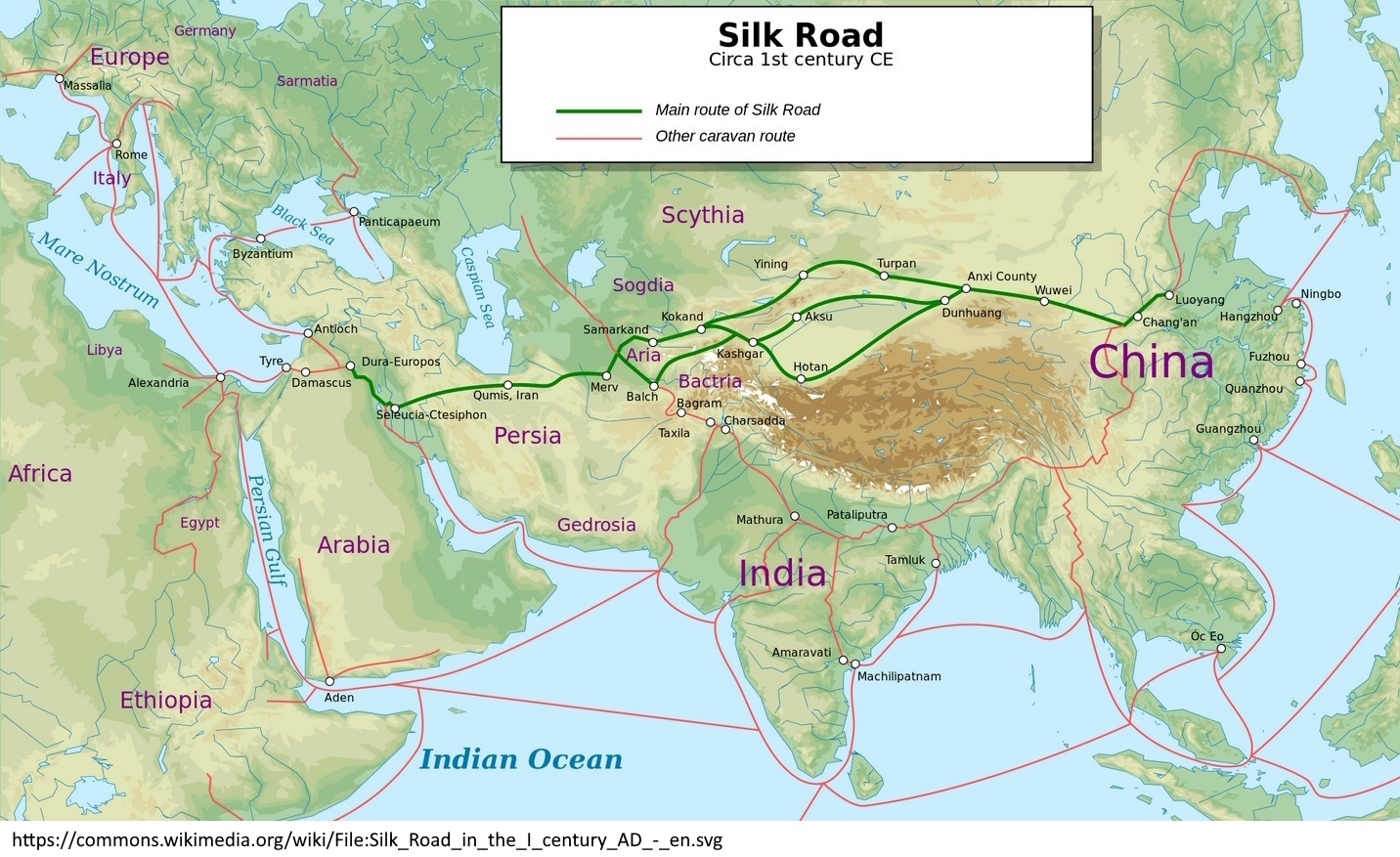

In order to transport the diamonds he purchased in India back to Europe, Tavernier used the same trading routes which had been used for centuries before his travels: The Silk Road. This trading route, connecting China to Europe via the Middle East, is said to have been used ever since the Han dynasty of China opened trade in about 130 BCE. This is the same route used by merchants of everything from silk to spices and from cotton cloths to tobacco. The diamonds traveled from India via Persia (modern Iran) and Arabia (modern Middle East), to Greece and Italy and from there to other European countries. The stones eventually arrived in cutting centers such as Amsterdam, Venice, Paris or Antwerp and sold to the European aristocracy and the wealthy merchant class.

Links to more knowledge

The Mahabharata in the Encyclopædia Britannica

South African Diamonds of Queen Elizabeth I (Cape Town Diamond Museum)

Books of interest

Diamonds. (Bruton, Eric. 1978, Chilton Book Company, Pennsylvania, USA)

The Mahabharata. (transl. Ball, Valentine. 2009, Penguin Classics, London)

Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I (Strong, Roy. 1963, Oxford : Clarendon Press)